Timothy Fitzgerald, “Joel Harrison on Facts and Values, Critical Religion and on Bruno Latour”

I recently (22 Nov 2017) found the text for Joel Harrison’s podcast “Facts v. Values: Can Religious Studies Be More Critical?”[i] when I wandered onto Facebook. I think my cursor inadvertently hovered over a small region of e-territory and the article jumped out at me.

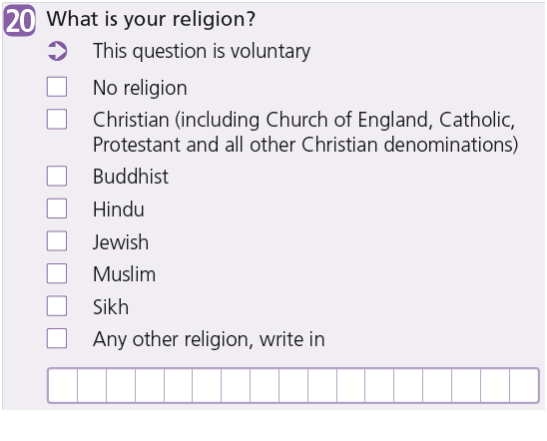

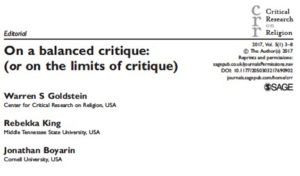

I was glad I saw the text and would like to contribute some discussion. Harrison’s piece is a defence of an editorial written by Warren Goldstein, Rebekka King and Jonathan Boyarin published in Critical Research on Religion (April 2016). This defence is turned against ‘critical religion’. I already responded to the CRR editorial several months ago, and I don’t know whether or not Harrison or Lucas Scott Wright has seen that (see CRR, vol. 4, 3: pp. 307-313, 2016).

Harrison’s article is also a discussion and advocacy of an essay by Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,” [Critical Inquiry 30, no. 2 (Winter 2004): 225-248. [https://doi.org/10.1086/421123]. Harrison thinks that ‘critical religion’ has valuable things to learn from Bruno Latour, and I think he is probably right. But I need to be clear what is being suggested. (more…)